Not that I have much time to write lately, but thought I should post that I have decided to blog over at macroeducation.org instead of on here. Hope to see you there as a reader or commenter!

Author Archives: devin

During the Knowledge vs. Skills discussion at #edcampfv (the Ed Camp in Maple Ridge on Saturday, December 3 – see my first post on the Ed Camp here) there were a number of insightful comments made and questions raised. One particular anecdote shared by a teacher (whose name I did not catch, sorry) has stuck with me since then, and I wanted to put some of my thoughts to paper.. er, keyboard/screen. (If by any chance the original storyteller reads this, please inform me if I totally misrepresented your story.)

To paraphrase, the story told concerned being stuck in a car with a few others for hours, held up by a highway accident, with nothing to entertain them except for their own conversations. Someone in the car looked outside, saw the stars, and a discussion about what stars were commenced. None of the passengers of the car being experts on stars, they had to discuss the sky, and through that process of discussion, many thoughts whirled, countless questions were asked, and curiosities piqued. The process and the questions turned out to be as interesting, if not more, than the answers we’d find in a textbook, on Wikipedia, or through Google.

The process of learning, through discussion, investigation, and experimentation—errors, missteps, and mistakes included—is more important than the ‘answers.’ I think that all educators realize this, but perhaps it’s sometimes forgotten, particularly in higher grades where test scores become more and more important.

Stars, the Cosmos, and Astronomy

The story shared by this teacher got me thinking about the role of astronomy in the history of science, learning and education. It also doesn’t hurt that I’m currently reading Coming of Age in the Milky Way by Timothy Ferris, which has heightened my fascination with the study of the cosmos and allowed me to make some connections to the anecdote at the Ed Camp, which I hope are not too far-reaching. Ferris’s masterpiece of popular science writing (nominated for the Pulitzer and awarded the American Institute of Physics Prize) takes us down the long and winding road of astronomy’s history, explaining how we have come to make some sense of our increasingly vast surroundings. He describes “the real history of science” as “a maze, in which most paths lead to dead ends and all are littered with the broken crockery of error and misconception.” The process—including the errors, refinements and subsequent evolution of our knowledge—are just as important as the discoveries, insights, and ‘answers.’

From Plato, Aristotle, and Ptolemy to Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton, the history of astronomy’s (and subsequently physics’s) giants parallels the evolution of our learning. More than any other field or subject, astronomy has been responsible for fueling our quest for knowledge. It’s said that the publishing of Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of Heavenly Spheres marks the start of the Scientific Revolution, Einstein called Galileo—who first turned a telescope to the sky—the ‘father of modern science,’ and Isaac Newton made the world quantifiable with his development of mass, force, gravitational laws, and calculus. We’ve made sense of our world, developing empirical reasoning and the scientific method, through the study of the cosmos and our place within them.

Perhaps Neil Postman was right in proclaiming that astronomy should be one of the three principal subjects (along with anthropology and archaeology) headlining the curriculum (see The End of Education, 1995). As someone who studied astronomy in my undergrad, I certainly am biased and can’t find myself disagreeing. It’s funny what a shared anecdote at an Ed Camp can lead me to think and write, and I look forward to more Ed Camps in the future, in hopes of getting more thoughts whirling and questions pondered. The process of discussion is exciting.

On Saturday, I attended my first ever Ed Camp at Garibaldi Secondary School in Maple Ridge. Ed Camps are often called un-conferences, in that they are similar to the more traditional professional development conferences teachers have attended for years, but have a less rigid agenda and are much more user-driven. The agenda is decided upon on the day of the event, and as far as I know, anyone can present or facilitate a discussion if they have a good idea. Think of it as a crowdsourced professional development day. For an overview of the process, watch this short video, and read a more thorough description of the day’s events here, on presenter Tyler Suzuki Nelson’s blog.

Rather than rehash all of the events of #edcampfv (as it was referred to on Twitter), I’d like to post some thoughts I had in response to the discussion facilitated by Tyler concerning the issue of Knowledge vs Skills.

Loosely put, the Knowledge vs Skills debate concerns the issue of how much emphasis educators put on the content to be learned in comparison to the process and skills required to learn that content. During the one-hour session, there was some debate as to how we define knowledge, as well as what we actually mean by skills. In my opinion, the two are not at all mutually exclusive, and shouldn’t really be pitted against each other from opposite ends of the spectrum. For aren’t skills often just acquired knowledge of how to do something? If you’re a student and your teacher teaches a lesson on the basic Trigonometry functions (Sine, Cosine, and Tangent), and then stays after school to show you how to use your calculator’s SIN, COS, and TAN buttons, are you acquiring knowledge of the trig functions, skills to compute them, or a little bit of both? I understand the need to differentiate between knowledge and skills, and it certainly makes for an interesting discussion, but I don’t think it’s as black and white as many seem to imply. Like most seemingly black-and-white distinctions in life, it turns out there’s much more grey.

In the digital age, the grey area of the definitions and uses of knowledge, memory, and intellect is more murky than ever. Countless times I’ve heard from students, colleagues and friends alike, “If I can Google it, why should I memorize it?” and while as a smartphone early adopter and Android fan I can relate, I worry about the dangerously slippery slope this may lead us down. If all of our memories become externalized, what will our brains be good for? I’m not exactly worried about this generation or even the next (okay, maybe I am a little bit), but thinking slightly longer term and wondering what the Googles, Wikipedias, and Twitters mean for our long-term futures, centuries down the road. Keep in mind that Google, Wikipedia, and Twitter are just 13, 11, and 5 years old, respectively.

I think we need to be aware that knowledge is more of a process, and not just a thing. Sure, we can Google anything we want and find answers, but do we really understand where it came from or what it means? Simply equating knowledge with facts removes the process and history of the accumulation of knowledge from the equation, ignoring the shoulders of giants we’ve slowly been building upon. In The End of Education, Neil Postman calls this history of learning and knowledge the Great Conversation, illustrating the importance of tapping into the dialogue by quoting Cicero (p. 124): “To remain ignorant of things that happened before you is to remain a child… What is a human life worth unless it is incorporated into the lives of one’s ancestors and set in a historical context?”

I think that by relying on the instant information of the digital age, we run the risk of losing much of the process that our ancestors have developed in refining and acquiring knowledge. We need to be careful not to equate information, which is little more than a message comprised of symbols, with knowledge, which is much more all-encompassing and ultimately more valuable.

Postman goes on to explain the importance of the process of education and the evolution of knowledge, and why we must acknowledge the role our ancestors played in its accumulation and development:

“When we incorporate the lives of our ancestors in our education, we discover that some of them were great error-makers, some great error-correctors, some both. And in discovering this, we accomplish three things. First, we help students to see that knowledge is a stage in human development, with a past and a future. Second, we acquaint students with the people and ideas that comprise “cultural literacy”—that is to say, give them some understanding of where their ideas come from and how we came by them. And third, we show them that error is no disgrace, that it is the agency through which we increase understanding.”

In a digital age, if students are taught that knowledge is what Google tells them it is, where’s the room for error? Are we aware of where the knowledge—or more aptly—the information, came from?

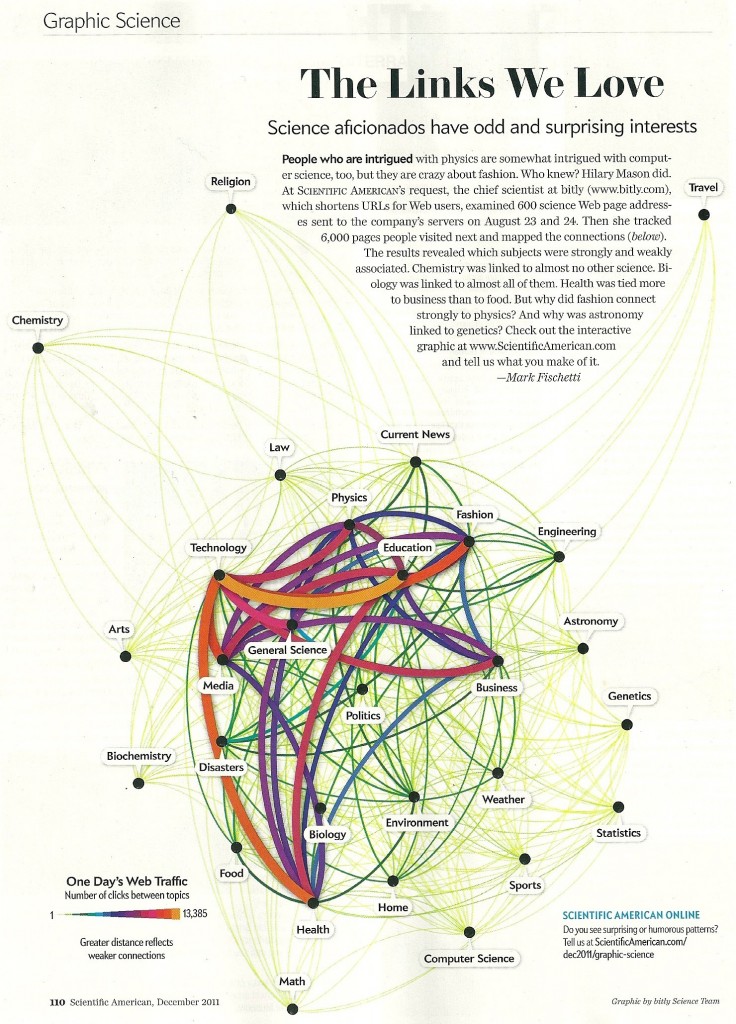

I thought that the Graphic Science piece on the last page of the latest Scientific American magazine ( Dec. 2011 issue) was pretty interesting. I scanned the image in from a paper-based copy of the magazine, and then shortly afterwards realized that the graphic was also available, in a superior interactive version, on the SciAm website. Someone remind me why I buy magazines again…

I think the study suffers from using a sample size (600) that is much too small, and much of what we see can probably be contributed to coincidence more than anything. That being said, I don’t think you can look past the obvious connection between people interested in both technology and education.

It’s funny, because traditionally education is an under-funded sector that often lags behind business, media, and science when it comes to adopting new technologies. What can account for the strong link between technology and education as shown above? Are a disproportionately large number of teachers using bit.ly? Are we seeing a grassroots movement of education reform, with technologically-savvy teachers using Twitter to network and collaborate? Are private educational institutions with more funds than their public counterparts more likely to be tightly linked with technology?

In reality, this is simply a small-scale study that yields more questions than answers. It’s not clearly explained how the sites were categorized, and we can’t hope to make any conclusions from it. But as Marshall McLuhan showed, it’s often more fun and instructive to talk about the questions than the answers.

In describing the wheel, language, the alphabet, the written and printed word, the telescope, Newtonian mechanics, the radio, and the television as technologies, McLuhan shows that studying human cultural evolution is essentially a study of the development of our technologies, which we use to learn about and adapt to our environments. He points out in 1969 that technology is much more than just a tool, and that the “the total-field awareness engendered by electronic media is enabling us — indeed, compelling us — to grope toward a consciousness of the unconscious, toward a realization that technology is an extension of our own bodies. We live in the first age when change occurs sufficiently rapidly to make such pattern recognition possible for society at large.”

If education really is life itself, as John Dewey said, then technology as defined by McLuhan is certainly forever intertwined with education. The evolution of our technologies has really been the story of the efficiency of information and the literacy we’ve developed to transmit it. Language, numbers, the alphabet, the printed word, and now, media such as Twitter and text messages have increasingly allowed us to transmit more information, while saying and using less. Education is built upon literacy – of numbers, words, and ideas. The forms of literacy have always been evolving as new technologies create new media. From the spoken word to the written word, from the printed word to television, it’s always been the case that we must educate to keep up with the growth of new technology, while being careful to not entirely leave behind what we gained from the old. Of course in the 21st century, with the pace of change relentless, this is harder than ever, but it’s not impossible. All generations have thought their own present time had a pace of change that was relentless.

While far from conclusive, I think that this graphic hints at this inseparable relationship between education and technology, although in all honesty, the strong link is most likely simply due to a lot of nerdy teacher-folk who spend a lot of time on the internet. (I would know.)

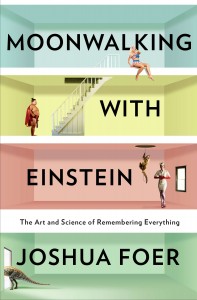

I recently read a fun little book called Moonwalking With Einstein by Joshua Foer, who I just researched and realized is the younger brother of writer Jonathan Safran Foer (Everything is Illuminated, Eating Animals, and more). Despite its title, the book is not about Michael Jackson’s trademark dance move, nor Albert Einstein. The subtitle, The Art and Science of Remembering Everything, is a bit more indicative of the subject matter. (The title comes from a mnemonic technique Foer used, in which a person or object is imagined to perform a memorable action.)

I recently read a fun little book called Moonwalking With Einstein by Joshua Foer, who I just researched and realized is the younger brother of writer Jonathan Safran Foer (Everything is Illuminated, Eating Animals, and more). Despite its title, the book is not about Michael Jackson’s trademark dance move, nor Albert Einstein. The subtitle, The Art and Science of Remembering Everything, is a bit more indicative of the subject matter. (The title comes from a mnemonic technique Foer used, in which a person or object is imagined to perform a memorable action.)

Foer covered the 2005 U.S. Memory Championship (yes, that really exists – with events such as Names and Faces, Speed Cards, and Poetry) as a journalist, and became entranced by the underworld of competitive memorizers. He spent the next year training for the 2006 championship, and this book chronicles his trials and tribulations. In addition to learning about the peculiar world and zany characters of the competitive memory circuit, Foer also investigates the act of memorization itself, its history, and its place in a world where virtually all of our memories have become externalized in the form of books and more recently, extremely well-indexed websites. Foer discovers that most competitive memorizers make use of an ancient Roman mnemonic device known as the method of loci, more commonly as the memory palace. Using the technique, memorizers conjure up mental images of well-known places from their lives, such as a childhood home or a favourite workspace. When memorization of a list or set of numbers is needed, the memorizer mentally walks through the palace, placing items on doorsteps, piano benches, and staircases, which makes the process of recall a simple matter of visualization of locations which are already well known. The items on the list are made physical and given context, at least in the person’s mind.

The techniques were developed in a world that predates the written word, when vast internalized memories were a sign of great intelligence. In a world of Google and Wikipedia, with knowledge and facts at our fingertips, are we losing the art of memorization, and does it really matter?

On education:

Foer’s book got me thinking about how, what, and why we test students in the classroom, and he delves into the subject of education on numerous occasions. He interviews a Mr. Matthews, who works with a group he calls “The Talented Tenth” at a high school in the Bronx, training them in memorization techniques to help them compete in memory competitions, and more importantly, on their exams.

Foer ponders the purpose of schooling:

“The success of Matthew’s students raises questions about the purposes of education that are as old as schooling itself, and never seem to go away. What does it mean to be intelligent, and what exactly is it that schools are supposed to be teaching? As the role of memory in the conventional sense has diminished, what should its place be in contemporary pedagogy? Why bother loading up kids’ memories with facts if you’re ultimately preparing them for a world of externalized memories?â€

“I don’t use the word ‘memory’ in my class because it’s a bad word in education,†says Matthews. “You make monkeys memorize, whereas education is the ability to retrieve information at will and analyze it. But you can’t have higher-level learning — you can’t analyze — without retrieving information.â€

“You can’t learn without memorizing, and if done right, you can’t memorize without learning.â€

He later interviews the controversial Tony Buzan, best known as the creator of the Mind Mapping technique. Buzan makes an important point that I certainly agree with, stating that “Students need to learn how to learn. First you teach them how to learn, then you teach them what to learn.†I think that sometimes we focus so much on the content, that we forget about the process. Say what you want about mind mapping and memory palaces, but they at least bring some focus to the development and cultivation of the learning process itself, rather than bludgeoning the student with facts, figures, and dates.

On books:

In the chapter called The End of Remembering, Foer also delves into some interesting observations about the evolution of the book, which struck me as very McLuhanesque.

“As books became easier and easier to consult, the imperative to hold their contents in memory became less and less relevant, and the very notion of what it meant to be erudite began to evolve from possessing information internally to knowing where to find information in the labyrinthine world of external memory.â€

“Now we put a premium on reading quickly and widely, and that breeds a kind of superficiality in our reading, and in what we seek to get out of books. … If something is going to be made memorable, it has to be dwelled upon, repeated.â€Â

After walking through Chapters and BestBuy recently and seeing the explosive growth of eReaders and tablets this holiday season, I have to wonder what our books are evolving into. Are we becoming even more superficial in our reading, as we read quickly and widely, dwelling upon nothing? With thousands of books in a tiny <$200 device, and millions more just a download away, are we changing the very nature of what it means to be a book? I’d like to be optimistic and hope that the new technologies of eReaders and tablets will inspire and encourage a new generation of readers, but the pessimist in me worries that the fancy apps, games, and communication capabilities of the devices will prove to be more attractive than the hundreds of pages of text buried within ebooks.

I am starting to feel like a bit of a Luddite, with my ever-growing collection of good old fashioned books taking up more and more space on my shelves, with the dog-eared pages and penciled-in notes a reminder of the slowly-read books I’ve dwelled upon over the years.

Final thoughts:

Moonwalking With Einstein is a fun read, full of quirky stories, some light science, and insightful ponderings about the history and future of our brains and our memories, both internal and external. Definitely worth a rental from the library at the very least.

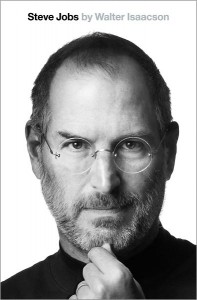

The new Steve Jobs biography is an incredible read so far. Perhaps it’s because most of this is new to me (I’ve never been much of an Apple fan or followed the Steve Jobs story) or perhaps it’s because Walter Isaacson is an extremely engaging writer. Regardless of why, I’m greatly enjoying the read about the fascinating depth of the polarizing Steve Jobs, the birth of Silicon Valley, and the rise of Apple.

In the opening chapter, entitled Childhood, there are a number of passages and quotes that stood out to me as being oh-so-true in regards to education. Here are a few of them:

On school and curiosity:

Even before Jobs started elementary school, his mother had taught him how to read. This however, led to some problems once he got to school. “I was kind of bored for the first few years, so I occupied myself by getting into trouble.” It also soon became clear that Jobs, by both nature and nurture, was not disposed to accept authority. “I encountered authority of a different kind than I had ever encountered before, and I did not like it. And they really almost got me. They came close to really beating any curiosity out of me.”

His parents’ view of the situation:

“Look, it’s not his fault,” Paul Jobs told the teachers, his son recalled. “If you can’t keep him interested, it’s your fault.”

Both of his parents, he added, “knew the school was at fault for trying to make me memorize stupid stuff rather than stimulating me.”

On his fourth grade teacher:

“I learned more from her than any other teacher, and if it hadn’t been for her I’m sure I would have gone to jail.”

After starting middle school at Crittenden Middle, located in a neighborhood filled with ethnic gangs, Jobs pleaded with his parents:

“I insisted they put me in a different school. When they resisted, I told them I would just quit going to school if I had to go back to Crittenden. So they researched where the best schools were and scraped together every dime and bought a house for $21,000 in a nicer district.”

On the counterculture of the late 1960s:

It was a time when the geek and hippie worlds were beginning to show some overlap. “My friends were the really smart kids,” [Jobs] said. “I was interested in math and science and electronics. They were too and also into LSD and the whole counterculture trip.”

Steve Jobs didn’t fit in to the traditional classroom, and it took one very good fourth grade teacher to keep him motivated and engaged. I wonder how many future “geniuses” (and I use the term cautiously) have had their curiosity beaten out of them and their motivation stifled at a young age? Did they go on to do great things anyway?

I highly recommend picking this book up. It’s only $25 at Chapters – not bad for a brand new hardcover book that clocks in at nearly 600 pages.

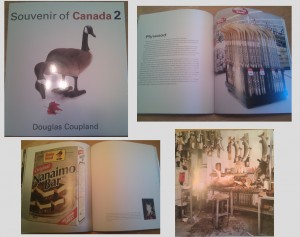

The book's cover (left), and two pages expressing the idea that "We look at the present through a rear-view mirror."

A couple of weeks later I found Douglas Coupland’s Souvenir of Canada 2, which, like McLuhan’s Massage, is dominated by graphics rather than text.

I’d estimate that both books’ pages are comprised of about 20% text, and 80% graphics or white space. Coupland’s collection of Canadian artifacts is humorous, simple, and understated. It’s the kind of book you leave on your coffee table, to have your friends and family mull over the images of Nanaimo Bars, hockey sticks, and a hunter’s workbench.If we all shift to reading e-books, will anyone leave books on their coffee tables anymore? The book’s charm lies partly in its physical nature, and its mostly white cover with the Canadian goose begs for it to be picked up and skimmed through. Can you skim through an e-book? Could this book even exist as an e-book? Would anyone want to publish it? Would anyone want to read it?

Perhaps authors and publishers are well on their way to figuring out how to make unique graphic-heavy books come to life electronically. The next generation of tablets looks promising, and I’ve seen children’s picture books look incredible on an iPad, complete with crisp graphics and even animations. Who knows what the future of reading looks like? History has shown us that media is full of surprises.

Sure, we’re getting great new mediums to tell stories, but a part of me is wondering what we’re giving up in the process. Neil Postman, a friend and advocate of Marshall McLuhan, built upon many of McLuhan’s ideas in his countless books, essays, and lectures. He noted that when new mediums take over, “the result is not the old culture plus the new medium, but a new culture altogether.” What is our new culture of reading going to look like? Are books still extensions of the eye, something more, or something less?

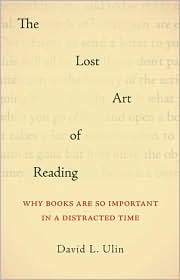

I recently read The Lost Art of Reading: Why Books Matter in a Distracted Time by David L. Ulin. I started it at approximately 11:00PM, and next thing I knew it was after 2:00AM, and I was nearing the end. I hadn’t read a book in a single sitting in years – I’d become too easily distracted by my smartphone, PVR, and laptop.  The Lost Art of Reading is not a long book, with only 150 short pages, and in fact you could probably classify it as an extended essay rather than a novel. I highly recommend it for anyone who’s ever categorized their personal library or smiled at the smell of a large, slightly musty used book store.

The Lost Art of Reading is not a long book, with only 150 short pages, and in fact you could probably classify it as an extended essay rather than a novel. I highly recommend it for anyone who’s ever categorized their personal library or smiled at the smell of a large, slightly musty used book store.

Ulin begins with the tale of his teenage son who is forced to not only read but annotate The Great Gatsby for homework, which causes his son to complain that “it would be so much easier if they’d let me read it.” After finally finishing the book, Ulin’s son suggests “This is why reading is over. None of my friends like it. Nobody wants to do it anymore.” If you’ve talked to a teenager recently who owns a smartphone, laptop, and video game system, you’ll realize how realistic this is. How many teachers have ruined teenagers’ interests in reading in some similar manner? The tale of his son’s Great Gatsby homework is woven throughout the essay, as Ulin deliberates his son’s proclamation, wondering if perhaps he’s right. He reflects on his own childhood, and his obsession with books, book stores, and authors, noting that he “frames the world through books.” This book critic loves reading and everything associated with it, including wondering about what the future of reading will look like.

This book had a lot of really great passages which I dog-eared, and I hope it’s okay to share them. If nothing else it should encourage everyone to go out and purchase this book (no, that’s not an affiliate ad) – it’s a great quick read. The first passage that struck me was Ulin’s description of his teenage bookshelf.

On Bookshelves:

Ulin writes of  the bookshelves he had as a teenager, and how he arranged his books on large “floor-to-ceiling shelves stretching across one long wall of my bedroomâ€, with his favourite authors “on a shelf in the center of the wall, everything else radiating outward from that core. In my mind, this was the library as virtual city, a litropolis, in which the further you were from the axis, the less essential a story you had to tell. To populate this city, I bought books at sales and in secondhand shops, by writers I often didn’t know.”

“Some of them I read (….) and some I never got to. But there they were, all of them, on those shelves together, my attempt at mapping the literary city in my mind. Although I don’t want to make too much of this, looking back I can’t help but see it as a strategy for turning concrete something that might otherwise have remained the most elusive of abstractions, as if only by thinking metaphorically might I take my interests, tastes, desires, even my aspirations, and make them three-dimensional and solid in the world.â€

Isn’t that what a bookshelf really is? It represents your interests, tastes, desires, and in the books you have purchased but not yet read, perhaps some of your aspirations. Books give form to these ideas, making them substantial and tangible.

Ulin’s voice is ultimately optimistic (yet realistic), as he explores what it is that reading has to offer us. Next I’ll take a look at what book stores mean to him.

Review of The Google Effect (full PDF here)

Tara Brabazon contends that due to the nature of Google, blogs, and wikis, we are coming to value popularity more than quality, and as a result, we are seeing a flattening of expertise, which she coins The Google Effect. Because Google’s top results are generated by a complex algorithm which in layman’s terms can be boiled down to “more traffic and clicks = higher search results†we’re seeing the popular items atop the heap, leaving the higher quality (but less popular) items to fall down the search results to the 2nd, 3rd, or 798th page.

Brabazon makes some valid cautionary points regarding Google, blogs, and wikis. The vast majority of us never look past the first page of Google results for many queries, never delving in with much depth in to a topic. Nicholas Carr deemed this outcome of our internet-addicted lives The Shallows, a (Pulitzer finalist) book about the effect the internet is having on our brains. The book was developed from Carr’s essay Is Google Making Us Stupid? in which he presented a thesis which is somewhat similar to Brabazon’s. He wonders if we are becoming ‘pancake people’ – with a wide but flat knowledge base – knowledgeable in many areas, but experts in none. Carr differs from Brabazon in that he presents his thoughts as objective musings rather than subjective criticisms.

Brabazon confirms her elitist frame of mind early, firmly stating that “As blogs continue to fill the Web with the bizarre daily rituals and opinions of people we would never bother speaking to at a party, let alone invite into our homes, there has never been a greater need to stress the importance of intelligence, education, credentials and credibility.†Perhaps that is a benefit of the internet – that we are exposed to more opinions and viewpoints than we would allow ourselves to in the analog world? Thomas L. Friedman would say so, as he expressed in The World Is Flat – his ode to globalization and the levelling of the playing field brought upon by the internet.

And what about the supposed wisdom of crowds? Aren’t we told that as a crowd, our collective intelligence is increased? Jeff Howe’s Crowdsourcing, Clay Shirky’s Cognitive Surplus and Don Tapscott’s and Anthony D. Williams’ Macrowikinomics are three (popular – oh no!) books which have illustrated the power and capabilities of our networked communities, using a wide range of examples including the open source community (Linux, Firefox, WordPress, etc), networks of amateur astronomers aiding professionals (GalaxyZoo.org), the use of social media to save lives in Haiti and Japan during devastating earthquakes, and the amazing capabilities of microlending website Kiva.org, which has facilitated nearly 300,000 loans totalling more than $200 million dollars, primarily assisting small businesses in third-world countries.

I’ve spoken to academia at this university about these particular books, and had the authors’ arguments dismissed because they “wrote for a popular audience, rather than one that is scholarly.†I think this type of thinking is inherently flawed. To me it looks something like this:

Popular stuff is not peer reviewed

If something is not peer reviewed, it is low quality

Everything popular is of low quality

Perhaps I’m going out on a limb here, but I think that Brabazon’s line of thinking is only too common in the mindset of those who have developed their understanding in the academic environment of the industrial age. It’s extremely linear, top-down, and close-minded.

[Will we ever have another Copernicus or Einstein? Could an amateur astronomer or an obscure patent clerk, working in isolation, wow the world with a startling new theory? Or are we so caught up in the extensive peer review process of circular back-patting that our academics would not give these amateurs the time of day?]

Misinformation and the overvaluation of popularity versus quality is not exclusive to Google. One could argue that all media throughout history has suffered from this effect to some degree.

John Dewey cites Julian Huxley’s book Scientific Research and Social Needs in saying that “one aim of education should be to teach people to discount the unconscious prejudices that their social environments impress upon them.†This was written shortly after World War II in the wake of the Hitlerization of Germany through the propaganda of the press and radio which Dewey calls “two of the most powerful means of inculcating mass prejudice.â€

Dewey contends that “An intelligent understanding of social forces given by schools is our chief protection.†It was true in the era of print and radio, and it’s still true in the era of the internet.

I’ve heard teachers say, “We can’t just let them use Wikipedia – anyone can edit it!†which first makes me laugh, and then subsequently sad. It’s been well-documented that Wikipedia is just as accurate as Britannica, and has the benefit of being instantly editable when there is an error. Wikipedia is perhaps the most incredible and comprehensive collection of human knowledge ever assembled, comparable to Borges’ mystical Library of Babel, as James Gleick illustrates in The Information.

If the tool is there, we shouldn’t hide it from our students. New tools offer opportunities, and it’s up to educators to design meaningful activities which allow us to utilize the capabilities of our digital age, while educating our students on the process of how these tools work and what their limitations are. I agree with Brabazon in her belief that digital tools such as Google and Wikipedia should represent “the start of learning, not the end.†It’s up to us educators to acknowledge this, adapt to the 21st century, and not fear the massive changes we’re experiencing in the ways we consume media.

This is a review of Technophobia, an Isaac Asimov essay which appeared in 1982’s The Roving Mind. It’s an excellent collection of writing on all manner of topics: creationism and evolution in schools, the relationship between technology and science, and even beyond the solar system (and the present) in essays on space exploration prospects, the emerging computerized world, and even the hotels of the future. It’s sometimes eerie to read about his visions of our future world, writing in “The Ultimate Communication” that we will soon have “a universal videophone capable of transmitting and accepting sound and image. We would want it small and mobile, but very complex and versatile, and yet stable and reasonably foolproof.” Sounds a bit like an iPhone, Android or Blackberry smartphone, doesn’t it? He later goes on to write about how computers will be able to offer personalized learning, describing a system which sounds an awful lot like the Internet, which of course piqued my curiosity. (But I’ll leave that for another post.)

It’s sometimes eerie to read about his visions of our future world, writing in “The Ultimate Communication” that we will soon have “a universal videophone capable of transmitting and accepting sound and image. We would want it small and mobile, but very complex and versatile, and yet stable and reasonably foolproof.” Sounds a bit like an iPhone, Android or Blackberry smartphone, doesn’t it? He later goes on to write about how computers will be able to offer personalized learning, describing a system which sounds an awful lot like the Internet, which of course piqued my curiosity. (But I’ll leave that for another post.)

Technophobia

“I hate signing up for new websites!†“I don’t want to learn how to use some new computer program!†“Do we have to do this? Why can’t we just make a poster or a binder?†“I can’t keep up with these new laptops and phones! I like my old one better.â€

We’ve all heard something along these lines in all walks of life, but I’m finding that these sentiments tend to be much more prevalent in the world of education. I always thought that I was not very tech-savvy, but I was amazed at the level of incompetency in a variety of technological skills and the absence of motivation to learn new tools displayed by some of my colleagues at the start of the year, and was dismayed to find that the problem seemed to exist in most schools as well. Why is it that teachers and teacher-candidates seem so unwilling to learn new technologies?

I discussed my observations and concerns with some more tech-savvy friends and colleagues, and tried to pinpoint the nature of this unwillingness. Why is it that we are so against signing up for a new website, or switching to a different email provider? I recently picked up Isaac Asimov’s Roving Mind, as per the  recommendation of Maria Popova (7 Must-Read Books on Education), and was delighted to find that Asimov had articulated the problem more perfectly than I ever could have imagined, in his brilliant essay Technophobia.

Asimov defines technophobia as “a morbid fear of technological advance†and in a few short pages, provides examples (both general and personal), metaphorical comparisons, and remedies to the problem. Technophobia exists in a variety of forms, and Asimov focuses his essay on the form “that involves the fear of a new advance in technology on the part of those whose professional career is actually involved with technology, and who clearly stand to benefit from the advance.â€

“Human beings learn how to handle numerous complicated devices in their lifetimes. The learning is not always easy, but once the complications are learned – if they are learned properly – it all becomes automatic. The thought of abandoning it and learning something else, of going through the process again, is terribly frightening.â€

Asimov thus defines technophobia as “the fear of re-education†and explains that “we invent reasons for resisting the change, but the real reason is that we dread the process of re-learning.†We see this fear rear its ugly head in all shapes and forms: business executives refusing to implement new software, the American public fearing a transition to the much more logical metric system, and writers (Asimov included) who fought the adjustment from typewriters to computerized word processors.

Asimov uses the example of his resistance to the word processor (this was written in 1982) in order to illustrate some valuable insights. He resisted the transition to a computer from a typewriter not because he loved his typewriter, but because he had put so many hours into learning how to use that typewriter. He did not want to have to learn something new, especially when (as far as he was concerned at the time) the new tool offered little improvement in quality over the old tool. In 2011, I’d argue that point – as we now see just how fluid and dynamic digital text can be, and the freedom we have as a result. Asimov makes another good point in saying that “re-education must be recognized for the highly difficult (and even more so) embarrassing process it is.†He goes on to explain that he only agreed to switch to a computer when his publisher sent Radio Shack employees to his home, so that he could learn the new tool in private, away from the eyes of more experienced users of word processors.

I think that this is an important insight for educators who want to bring new tools into the classroom. Perhaps we can utilize virtual classrooms and blended learning in order to give students (and teachers) access to new websites and software from the privacy of their own homes, away from the judgmental eyes of their peers.