During the Knowledge vs. Skills discussion at #edcampfv (the Ed Camp in Maple Ridge on Saturday, December 3 – see my first post on the Ed Camp here) there were a number of insightful comments made and questions raised. One particular anecdote shared by a teacher (whose name I did not catch, sorry) has stuck with me since then, and I wanted to put some of my thoughts to paper.. er, keyboard/screen. (If by any chance the original storyteller reads this, please inform me if I totally misrepresented your story.)

To paraphrase, the story told concerned being stuck in a car with a few others for hours, held up by a highway accident, with nothing to entertain them except for their own conversations. Someone in the car looked outside, saw the stars, and a discussion about what stars were commenced. None of the passengers of the car being experts on stars, they had to discuss the sky, and through that process of discussion, many thoughts whirled, countless questions were asked, and curiosities piqued. The process and the questions turned out to be as interesting, if not more, than the answers we’d find in a textbook, on Wikipedia, or through Google.

The process of learning, through discussion, investigation, and experimentation—errors, missteps, and mistakes included—is more important than the ‘answers.’ I think that all educators realize this, but perhaps it’s sometimes forgotten, particularly in higher grades where test scores become more and more important.

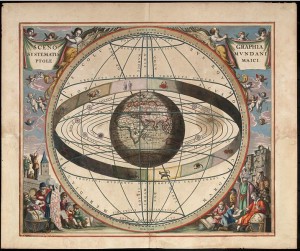

Stars, the Cosmos, and Astronomy

The story shared by this teacher got me thinking about the role of astronomy in the history of science, learning and education. It also doesn’t hurt that I’m currently reading Coming of Age in the Milky Way by Timothy Ferris, which has heightened my fascination with the study of the cosmos and allowed me to make some connections to the anecdote at the Ed Camp, which I hope are not too far-reaching. Ferris’s masterpiece of popular science writing (nominated for the Pulitzer and awarded the American Institute of Physics Prize) takes us down the long and winding road of astronomy’s history, explaining how we have come to make some sense of our increasingly vast surroundings. He describes “the real history of science” as “a maze, in which most paths lead to dead ends and all are littered with the broken crockery of error and misconception.” The process—including the errors, refinements and subsequent evolution of our knowledge—are just as important as the discoveries, insights, and ‘answers.’

From Plato, Aristotle, and Ptolemy to Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton, the history of astronomy’s (and subsequently physics’s) giants parallels the evolution of our learning. More than any other field or subject, astronomy has been responsible for fueling our quest for knowledge. It’s said that the publishing of Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of Heavenly Spheres marks the start of the Scientific Revolution, Einstein called Galileo—who first turned a telescope to the sky—the ‘father of modern science,’ and Isaac Newton made the world quantifiable with his development of mass, force, gravitational laws, and calculus. We’ve made sense of our world, developing empirical reasoning and the scientific method, through the study of the cosmos and our place within them.

Perhaps Neil Postman was right in proclaiming that astronomy should be one of the three principal subjects (along with anthropology and archaeology) headlining the curriculum (see The End of Education, 1995). As someone who studied astronomy in my undergrad, I certainly am biased and can’t find myself disagreeing. It’s funny what a shared anecdote at an Ed Camp can lead me to think and write, and I look forward to more Ed Camps in the future, in hopes of getting more thoughts whirling and questions pondered. The process of discussion is exciting.

It’s sometimes eerie to read about his visions of our future world, writing in “The Ultimate Communication” that we will soon have “a universal videophone capable of transmitting and accepting sound and image. We would want it small and mobile, but very complex and versatile, and yet stable and reasonably foolproof.” Sounds a bit like an iPhone, Android or Blackberry smartphone, doesn’t it? He later goes on to write about how computers will be able to offer personalized learning, describing a system which sounds an awful lot like the Internet, which of course piqued my curiosity. (But I’ll leave that for another post.)

It’s sometimes eerie to read about his visions of our future world, writing in “The Ultimate Communication” that we will soon have “a universal videophone capable of transmitting and accepting sound and image. We would want it small and mobile, but very complex and versatile, and yet stable and reasonably foolproof.” Sounds a bit like an iPhone, Android or Blackberry smartphone, doesn’t it? He later goes on to write about how computers will be able to offer personalized learning, describing a system which sounds an awful lot like the Internet, which of course piqued my curiosity. (But I’ll leave that for another post.)